A Totally Random Review of Undertale

This was originally written for a creative writing workshop, with the assignment being to write a review; I thought it was good enough to post here. Also: I purposely avoided spoilers here wherever possible. It’s inevitable to let some though, but any vagaries are likely due to this.

That video games are or can be art has been justified many times over with examples such as Shadow of the Colossus, with its stunning visuals and atmospheric feel, or The Last of Us, with its riveting and emotional post-apocalyptic adventure. For me, though, the most outstanding example is not a 3D, triple-A action-adventure game, but an 8-bit RPG developed by one person with help from his friends—and which managed to become one of the most iconic games of all time. If you spend a good amount of time around young people online, you probably know it. And there’s a good chance you may have guessed it already.

I’m referring to Undertale. If the name doesn’t ring a bell, here’s the short version: a budding composer named Toby Fox, after making some ROM hacks of the SNES game Earthbound, took a few years and, with help from others such as Temmie Chang, came up with his own RPG. Indie games by 2015 were an established niche; an Earthbound-inspired pixel art RPG wasn’t very novel. Yet Undertale rose to become one of the most acclaimed games of all time. Why? Well, a lot of reasons. Pretty much everything, really: the story, the characters, the music, and the gameplay are all interesting or innovative in some way.

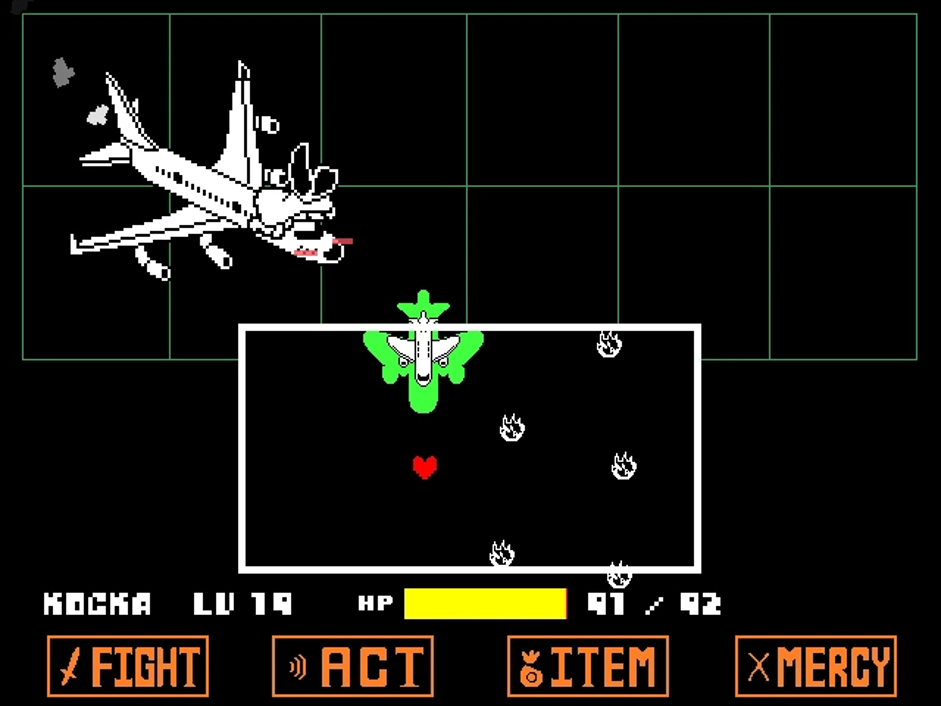

Some of Undertale’s quirks might go unnoticed to those unfamiliar with RPGs, but they’re apparent from the very beginning. Flowey the flower introduces us to “happiness pellets”, which turn out not to be so happy—they are, in fact, the bullets used in the battle mechanic. Soon you find yourself in a full battle, as the loving Toriel tries to keep you from entering the Underground for your own safety. Anyone familiar with RPGs will notice something immediately: the “Act” and “Mercy” buttons. They’ll also find that being on the receiving end of an attack isn’t passive like in Dragon Quest or Earthbound: you have to avoid the bullets to keep yourself from taking damage, in the same interface our floral friend showed us earlier. Oh, and those two weird button options? They’re how you end the battle peacefully. “Act” lets you talk to or interact with your opponent, and “Mercy” lets you spare them when they’ve been calmed.

This may seem convoluted, but it plays an important role in the entirety of the game, because how you choose to battle will change the game’s ending. The fate of the Underground and its residents is in your hands—you, the player. And this brings us to the less technical details: character and story.

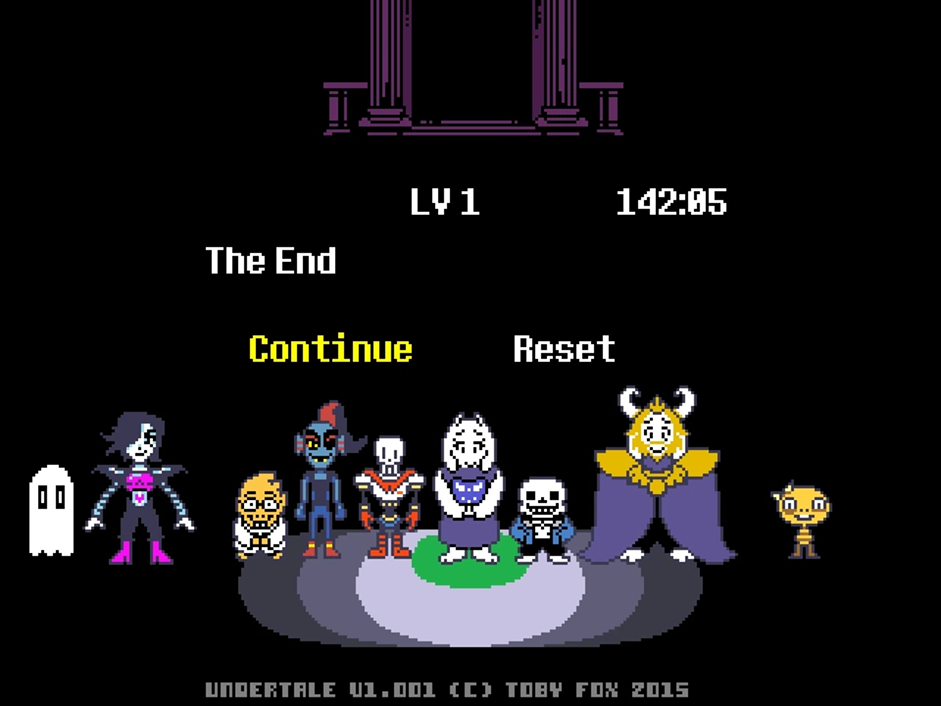

To say that a game’s characters are “well-written” is a compliment, but a rather vague one. It’s certainly true of Undertale: Sans, the second main character you meet, has become something of an internet icon, and pretty much anyone who’s played the game will tell you about their favorite characters. The caring Toriel, the lovably silly Sans and his charmingly awkward brother Papyrus, bad-ass soldier Undyne, depressed ghost Napstablook, anxiety-riddled scientist Alphys, robot TV star Mettaton, caring, sensitive, and conflicted king Asgore—I can go on, but in playing the game, you begin to connect with the Underground’s inhabitants in a way most games can only hope you would.

Undertale’s characters aren’t merely interesting creations: they have the potential to be your friend or your enemy. Sparing the main characters lets you befriend them. The game doesn’t force you to fight in any battle except one (no spoilers!), so you have the ability to change the entire game’s dynamic by what you choose to do. If you like a character, you can (almost always) avoid hurting them and instead try to de-escalate the situation. And if you don’t like them, you can kill them. As a consequence of this, the game puts the player in a position I haven’t seen another game do: the player’s choices are given a moral dimension, because the world reacts to how you choose to treat its inhabitants.

This flexibility is actually a pretty amazing feat on Fox’s part. There are three main types of endings (pacifist, neutral, and no mercy, aka “genocide”), with a total of 93 different endings based on your choices. All of them are intensely emotional. Fox has been careful to clarify that the game has no single, canonical ending, which further adds to the game’s intrigue.

It’s hard to convey the meta aspects of the game without giving spoilers, but suffice to say that these details, along with the metaphysics Fox gives his universe, all add up to make a game that comments on its game-ness without devolving into cynical self-awareness or overly theoretical metafiction. It’s also difficult to relay the game’s humor without just quoting it. And the soundtrack, too, is hard to give its due worth without writing an entirely new review—it’s become one of the most beloved game soundtracks, and for good reason.

If you haven’t played Undertale, you owe it to yourself to do it. If you’re a fan of film, theater, literature, or the “fine arts”, it may convince you of the power video games can hold as a narrative art form. If you’re familiar with RPGs, it’ll change how you look at the genre. And if you aren’t such a highfalutin fellow, it’s also a straight-up enjoyable game: funny, engaging, entertaining—just, well, fun. And I don’t know what better endorsement you can give than interesting, artful, and fun.